By Eric Ferrero, executive director

It’s been three months since Leah Sottile’s story on James Plymell’s death was published in High Country News, republished in other outlets and amplified in Longreads. It’s one of those stories that sticks with you for months after you read it.

With a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, Sottile took a deep dive into a particularly complicated case – Plymell had more than 100 interactions with local police over the years, and he struggled with mental health, addiction, and homelessness. She also dug into the broader issues Plymell’s case highlights: how small towns in the West (where homelessness rates are the highest in the country) criminalize homelessness and how police use of Tasers is minimized even when it ends in death.

I talked with Sottile about how to balance so many complex storylines in one longform piece, investigative reporting in rural communities, the importance of local media, and more. She shared terrific advice for other reporters, and talked candidly about the mental health challenges of reporting stories like this.

Q: You shared with me recently that this story presented a lot of new reporting challenges for you, even with all of your experience in longform narrative and investigative journalism. What were some of your biggest problems writing this story, and what did you learn that you’ll take into future projects?

James Plymell’s death was largely passed over by Oregon media, which was surprising because when I initially read the reports of it in October 2019, I had a gut feeling there was a story there to be told. That feeling came from the neatness of the existing narrative: that after being tased by members of the Albany Police Department, Mr. Plymell died, and his death was chalked up to drugs, heart problems or some combination of the two. To me, that felt like only one side of the story.

I knew I needed to review all available evidence in order to gain a full picture of what happened. A source had previously provided me with the body-camera footage, which showed what occurred was a much more complicated story. That body camera footage, which is harrowing, was where I started reporting. I was compelled by one moment in the footage, when the officers discussed that they’d encountered Mr. Plymell lots of times before. So, I figured, if he had, for example, pulled a gun on officers, fought them, or been violent in the past, records would show that.

Public records in Oregon aren’t really all that public, in that they cost a ton of money. There is an enormous barrier for freelance reporters like myself to get the necessary records to do responsible, complete journalism — which is unfortunate because, as seen by the lack of media coverage of Mr. Plymell’s death, if a someone like me didn’t express interest in his story and seek out a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, it would remain untold. That was one obstacle.

Another was when I finally got the requested records, one key audio interview was missing with the community service officer involved in this case, the first officer on scene. For weeks, Albany Police said they did not have it, and that it was with Oregon State Police. Oregon State Police said they didn’t have it, either. The longer these two agencies went back and forth, it brought up new questions: Why was it missing? What happened to it? What did it contain? Eventually I got the audio, which only happened from extreme persistence on my part.

The pandemic was an obstacle, obviously. For a story that involves an in-custody death, a marginalized community, and a small city or town, I typically would do all of my reporting in person. But that wasn’t really possible. So, I had to work the phone. I was lucky to get all of the phone numbers from Mr. Plymell’s cell phone, and so I called almost all of them, leaving messages, asking for people to call me back. Some people called me and told me to stop poking around. Others called and had lots to say.

The last obstacle was, perhaps, the most unexpected: the mental health issues I experienced from working on this story. I have reported on extremely difficult things in my career: murders, suicide, animal abuse, riots, terrorism. I figured I was pretty much ironclad. But this story required me to basically memorize the body camera footage of Mr. Plymell’s last moments, and so I watched it over and over and over again — each time, picking up new things I hadn’t seen the times before.

But after a while, I’d start breaking down while watching it. Serendipitously, while I was reporting this piece, High Country News offered a training with the DART Center about trauma from reporting. I learned that what I was experiencing was actually common for journalists. It wasn’t a weakness at all. It, and the help of a therapist, helped give me the tools to cope with doing difficult but necessary reporting.

Q: What tips do you have other journalists about investigative reporting in rural or semirural communities?

It’s a good question, and one I get asked a lot. In my experience, people live in rural places for lots of reasons, but one big reason is that they want to be left alone. Knowing that, a reporter would be remiss to think they can run into town, get a story and leave. Journalism in rural communities requires trust, time and, frankly, good manners. If someone offers you coffee, drink it. People have to believe that if they talk to you, it will be worth their time — but I think that’s true of reporting anywhere. Typically, I will introduce myself over the phone before I report in person, and then arrange an in-person meeting. Sometimes I’ll ask to be shown around a little bit by a local, and that’s something I really love to do — to see a place through someone else’s eyes.

“Place” is also very integral to my reporting process. I do tons of reading about a place before I go there. I review topographical maps. I read about historic fires and floods. I read about things that have got nothing to do with the story I’m working on, but when I finally arrive to speak in person, I have plenty to ask. And that surprises people. Sometimes people can’t believe I care that much.

Q: This is such a rich story with multiple layers. Can you take us into your writing process a little bit: How did you approach balancing Plymell’s personal story with the broader issues, and how did you develop the narrative structure?

Early in my career, I lived in Spokane, Washington, where a man named Otto Zehm died after being asphyxiated by police. Zehm was developmentally disabled. When the police killed him, it opened my mind up to a whole subset of in-custody deaths that don’t involve guns. It tuned my ears to listen for police stories that have nothing to do with guns. And perhaps that’s why I saw a story in what happened to Mr. Plymell where other reporters did not. Also, even earlier in my career, I founded a street newspaper that was primarily devoted to issues of people experiencing homelessness. I spent a great deal of time volunteering at crisis shelters, and as a young, aspiring journalist, it was clear to me that the stories of unhoused people were not being told. This was in 2001; this has not changed.

My goal was to show Mr. Plymell in all of his complexities — not as a martyr, or a hero, or a villain, or anything other than who he was. That meant telling the audience about his community, which happened to be the vast community of people experiencing homelessness in Oregon. I didn’t set out to write a story about the unhoused community when I saw the body-cam footage, but that is the story that required telling in order to understand the broader issue that brought the officers and Mr. Plymell together that day.

I spend a lot of time thinking about story structure, and for almost all stories I work on, I build massive timelines with every detail. For this piece, I made maps of every address where Mr. Plymell’s interactions happened. And then I drove from place to place, building scenes, trying to envision each scenario playing out. For every story, I spend a lot of time sitting in places, writing every detail I can see.

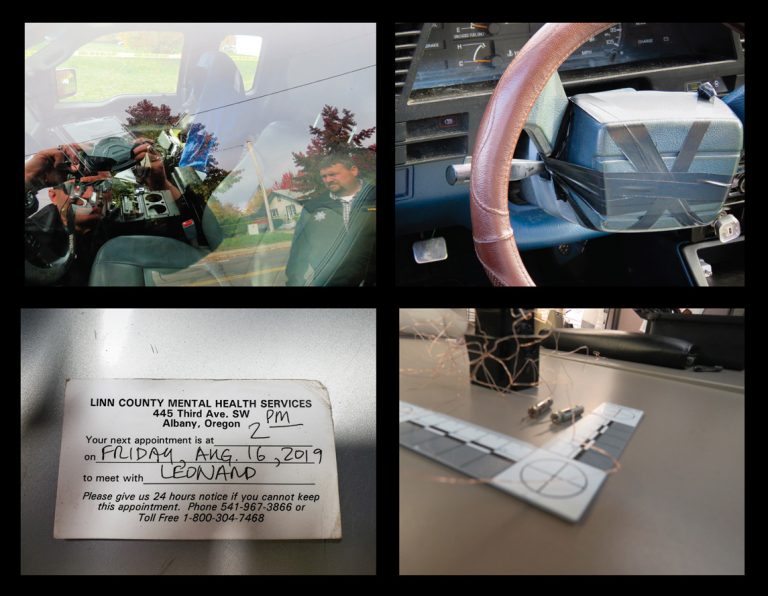

Q: I think the images with this story are part of why it stuck with me and resonated with so many other people. The photos you found on his phone bring us inside his day-to-day life in a really vivid way, and the photos and video of his death are disturbing. What went into deciding whether and how to use them?

I was very lucky to worth with an amazing team on this story, and High Country News Photo Editor Bear Guerra, very early on, said what impacted him most from the trove of public records we received was how mundane and normal the scene was. This was so important for me to hear in my formation of the story: to remember that police brutality happens everywhere, in every city and town. And I think it led to how Bear and Art Director Cindy Wehling chose the photos: We wanted to tell the truth of the story, show the entirety of the scene, but also provide insight into who this man really was.

Q: This is a story about a white man in a state with a tiny Black population, published during increased national conversation about racism in the criminal justice system. How did that factor into your decision to tell this story and your decisions about how to tell it?

I think every time someone dies in the custody of police, it deserves this sort of longform narrative investigation. If we are going to reckon with police brutality in a complete and total way, I think we have to look at all of the people who are dying at the hands of law enforcement. In Oregon, people experiencing homelessness and people with mental health issues often are those people.

Q: You’ve published in the New York Times Magazine, Washington Post, and other large outlets. Why was it important for this story to run in a regional nonprofit magazine, and what advice do you have for other journalists, partners and funders when they’re thinking about how to support regional nonprofit media?

I believe High Country News is one of the most important magazines in the country right now — and absolutely on the issues affecting the western United States. It is made by people who live in the West, who know the West, and are not caught up in stereotypes of the region. I knew that by doing this story for HCN, the people who live in Mr. Plymell’s community would be the ones reading it. In addition, HCN allows other publications to reprint our stories, and this story was picked up by the local newspaper and the largest newspaper in the state.