The Society of Environmental Journalists, which partners with the Fund for Investigative Journalism (FIJ) by recruiting mentors for FIJ grantees, is planning its 2016 conference in Sacramento California for September 21-25. Last fall, FIJ grantee Elizabeth Shogren attended the 2015 SEJ conference in Oklahoma, and filed this report:

Society of Environmental Journalist conference fieldtrip explores surge in induced earthquakes.

By Elizabeth Shogren, DC correspondent, High Country News

Soon after I arrive in Oklahoma City for the Society of Environmental Journalists annual conference, a former editor of mine, who lives here, tells me, almost with a shrug that his house shook twice just the week before. My colleague and many of his fellow Oklahomans have managed to maintain a high degree of nonchalance as they live through one the most mysterious environmental stories in recent years—the proliferation of earthquakes induced by oil companies injecting their wastewater deep into the earth. The hotbed is in Oklahoma, where two earthquakes a year measuring magnitude 3 or above would be normal. Starting in 2012, the state started measuring a few dozen a year of that magnitude. Last year, a whopping 585 measured magnitude 3 or above, and in the first nine months of this year, 647 did, according to state and US Geological Survey data.

Soon after I arrive in Oklahoma City for the Society of Environmental Journalists annual conference, a former editor of mine, who lives here, tells me, almost with a shrug that his house shook twice just the week before. My colleague and many of his fellow Oklahomans have managed to maintain a high degree of nonchalance as they live through one the most mysterious environmental stories in recent years—the proliferation of earthquakes induced by oil companies injecting their wastewater deep into the earth. The hotbed is in Oklahoma, where two earthquakes a year measuring magnitude 3 or above would be normal. Starting in 2012, the state started measuring a few dozen a year of that magnitude. Last year, a whopping 585 measured magnitude 3 or above, and in the first nine months of this year, 647 did, according to state and US Geological Survey data.

I’m one of dozens of reporters to pile into a bus for a daylong SEJ fieldtrip to learn about hydraulic fracturing, the drilling technique behind the US energy boom, and the earthquakes. On board are several experts, including US Geological Survey seismologist George Choy who recently joined an agency team focused on the induced earthquakes. So far, the earthquakes have caused limited damage, but once faults are activated, more quakes can follow. This region of the country is vulnerable because structures from homes to bridges weren’t built with earthquakes in mind. “We don’t know what the maximum size earthquake will be,” says Choy.

“People should certainly be concerned that the earthquake hazard has increased.”

Experts from science, industry and government have far more questions than answers about what’s causing the earthquakes, and what would stop them. They believe the quakes are linked to oil and gas companies injecting wastewater underground. But why are there so many earthquakes in Oklahoma and not in other drilling centers such as North Dakota’s Bakken? And why has the seismic activity in Oklahoma rapidly increased only recently when companies have injected wastewater underground in Oklahoma for 60 years? Could it be that some tipping point was recently reached because of the accumulation of water injected over the years? Or might the quakes be connected to the depth of the disposal wells or rate of injections? These are just some of the many questions experts have.

One key difference between oil and gas production in Oklahoma and other parts of the country is that more water comes up with every barrel, so there’s a lot more to dispose of. The total amount of water injected is tremendous and has grown significantly in recent years, from 800 million barrels of water in 2009 to nearly twice that, 1.5 billion barrels in 2014, according to Kyle Murray, hydrogeologist from the University of Oklahoma, one of the experts on the bus. Two-thirds of that water was pumped into a layer of earth called the Arbuckle formation, which experts suspect is related to the quakes. How much water was injected before 2009 “is a big question mark,” says Murray. Volumes weren’t tracked well because ”there was very little concern about seismicity,” he adds.

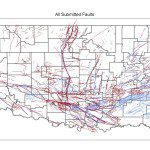

Kim Hatfield from Crawley Petroleum said that the industry has tried to help solve the mystery and avoid more quakes by handing over its proprietary seismic data to the state. This helped fill in a map of where the faults are. The Oklahoma Corporation Commission, the agency that regulates the industry, consults the fault map when deciding whether to permit new injection wells.

Choy agrees the industry data can help avoid drilling and injecting in areas that are obviously risky but he cautions: “obtaining industry data is not a panacea. The locations of most faults are unknown. Many times we find out about a fault only after a series of earthquakes occur which delineate a pattern.”

The bus tour stops at an injection well, but not in a region where the quakes are occurring. Michael Teague, Oklahoma’s secretary of energy and environment, meets the group and fields questions about his tiny agency’s efforts to understand the earthquakes.

“We believe it’s related to injection, now we’re trying to figure out what do we do?” Teague says.

One theory is that the quakes were caused when drillers inadvertently drilled through the Arbuckle formation into the formation below, called the basement. So the state limited the depth companies were drilling their disposal wells. “I can’t tell you we’ve seen a decline,” Teague adds.

He was asked why the state hadn’t followed the example of Kansas, which starting in March restricted volumes of water injected. “We don’t know if volume is the answer,” Teague say. The Oklahoma Corporation Commission in September did shutdown and reduce volumes at injection wells near Cushing, Oklahoma following earthquakes in that area, which is a major trading hub for crude oil. (Later in the fall, the commission announced new actions reducing volumes at injection wells near earthquakes in several parts of Oklahoma including Cushing, Medford, Fairview, Cherokee and Crescent.)

Would Oklahoma consider a moratorium on injection given the surge in earthquakes? Teague says that would be out of the question because of how dependent Oklahoma is on the oil and gas industry for jobs and revenue. “I don’t see us doing a ban,” says Teague.

He’s looking for other solutions for the wastewater, such as finding ways to treat it so it can be used above ground. But his resources to seek remedies are shrinking. Teague’s office is one of the many state functions funded by industry. His revenues were $125,000 a month a year ago, and this fall they were down to $50,000 a month. In the meantime, his agency is trying to keep the public informed about the earthquakes and what state government is doing to respond to them through the website: http://earthquakes.ok.gov.

Graphic: Oklahoma fault map supplemented with industry data. The Blue fault tracks are the ones that the Oklahoma Geological Survey previously had in their catalog. The majority of those faults are in the shallower sedimentary section and are not terribly useful in the work on seismicity. The Red fault tracks represent data supplied by industry on the basis of their 3D seismic surveys and these focused on faults in the Arbuckle and the Basement below that. This map has been used by the Oklahoma Corporation Commission in their approval process for injection wells.