By Eric Ferrero, Executive Director

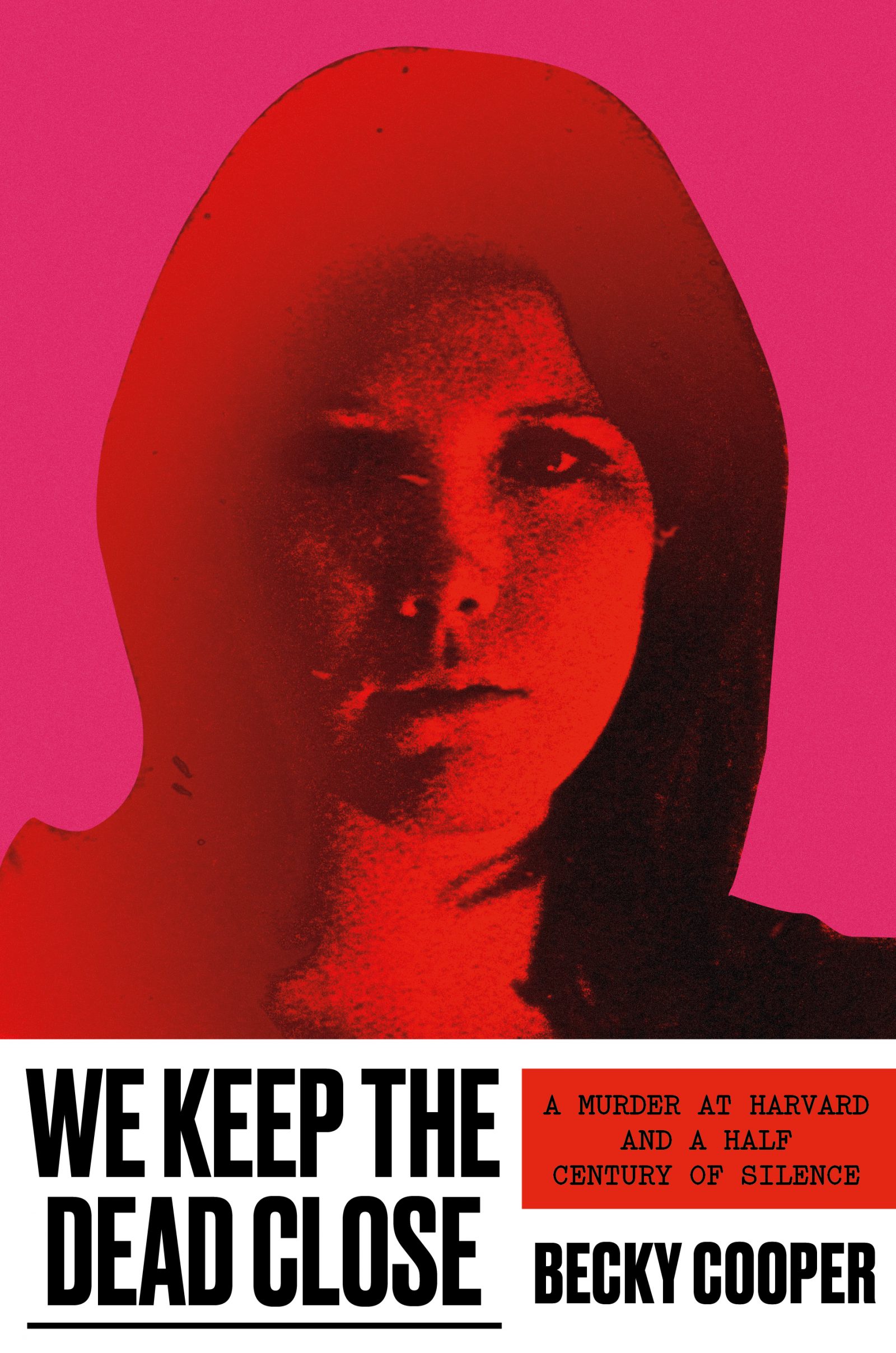

“We Keep the Dead Close,” by Becky Cooper, was published in November and quickly became one of the most acclaimed books of the year. Digging into a 1969 unsolved murder at Harvard, Cooper pulls back the curtain on misogyny in academia and true-crime culture — and takes readers inside a decade of dogged investigative journalism.

Cooper applied for a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism in 2017 to cover some of her reporting costs. At the time, she was working as David Remnick’s editorial assistant at The New Yorker. In her grant application, she explained that she planned to quit her job to work on the investigation full time. She already had solid research, good sources and a strong investigative plan. She needed financial support to do it — and she got that from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

“We Keep the Dead Close” has been profiled in the New York Times, Washington Post, National Public Radio and Vogue. It has already been named one of the best books of the year by Amazon, Publishers Weekly and Glamour.

I asked Cooper to share more about the decade she spent researching and reporting the project and what advice she has for other investigative journalists.

This book is a fascinating story about a case and about society — and it’s also a story about rigorous, dogged research. Jessica Wakeman called the book “a master class in how to do investigative reporting,” and the Philadelphia Inquirer called you an “obsessive researcher.” What were some of the most valuable research tools and techniques you used?

I wish I had something more exciting to say, but most of this book was done with old-fashioned reporting techniques: a ton of archival research in Harvard’s many libraries and in the Cambridge Historical Commission for instance, in addition to dozens and dozens of interviews. I worked my way into Jane’s college world by finding a digitized copy of her freshman register, which listed her dorm. I wrote down the name of every freshman who was in the same dorm and used a combination of Nexis and Harvard’s alumni database to track down their contact information. Then it was just a matter of cold calling.

For the FOIAs and public information requests, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press’s resources were invaluable, and casetext.com was very helpful in finding and citing precedent for my appeals.

The trust you built with Jane’s brother, Boyd, at the outset clearly helped in parts of your reporting. What tips do you have for reporters on how to build that kind of trust, especially on sensitive and difficult stories?

I tried to do as much research as I could before talking to people close to the story both because I wanted to have as much to talk about as possible and also because it felt like a matter of responsibility. I think most reporters will say that listening and being genuinely interested are the keys, and I agree, but I think one of the ways you can demonstrate that sincerity of interest is by coming prepared.

It’s also important to give people time. Don’t rush the interview just trying to get the facts. Ask around the things you know you want to know: how it felt, how they knew that, how it’s changed for them over time. Trust takes a long time to establish, but so does the understanding of what questions to ask in the first place.

I also operated on chains of trust whenever possible. It was Jane’s best friend from college, for instance, who put me in touch with her brother.

You extended this project and spent a couple of extra years on it, partly because the #MeToo movement began to shift the narrative within academia. How did that reckoning help shape your work?

My investigation about a fifty-year-old murder had already forked into an examination of gender discrimination and sexual misconduct in academia by the summer of 2016, a full year before the #MeToo movement began. But for that year and a half, it wasn’t easy to get people on the record talking about their experiences. Many people were still afraid either because it still felt so fresh, or because they didn’t want to be seen as the kind of people to complain, especially since the power structures that fostered a culture of silence were still in play, and/or because they felt their experiences didn’t add up to criminal action, so they felt their stories were somehow less than, or just gossip, or not worth the hit their career would take. When the #MeToo movement took hold though, people in general — were much more willing to come forward. I think part of it is that it offered a frame for otherwise isolated experiences — “it wasn’t just me” — and because it offered the promise of a cultural shift that was finally, maybe, starting to hold this behavior to account.

This started out as a four-part series of articles and evolved into a book. What advice do you have for other investigative journalists who get deep into a story and think they might have a book?

I’d say the most important thing — whether it’s long articles or a book — is to make sure you’re crazy passionate about the project because it will consume your life. Then make sure you’re constantly open to having the investigative material shape whatever you’re writing. Pragmatically speaking, though, it may be necessary to shake the investigative threads loose (nevermind easier to get a book deal), by writing a shorter article first. The Boston Globe Spotlight Team’s article was crucial in raising awareness of the Middlesex DA’s refusal to release the police files of a 50-year-old murder, but in the absence of that, I might have needed to publish an article in order to put public pressure on the DA’s office to make the investigation active.

I looked back at your grant application this week and was struck that you said you needed help with both reporting costs and some basic living expenses because you were quitting your job at the New Yorker to work on this project full-time. Among other things, you asked for $84.50 a month for a Charlie Card to get around Boston via public transit and $180 a week for groceries. How can funders, publishers and others make this kind of reporting possible and sustainable for more reporters?

I think if we’re serious about getting a wider variety of stories pursued and more reporters represented, we need to recognize that covering base living costs is as integral to the reporting process as a Nexis subscription. I also think it’s crucial to raise awareness of these funding opportunities. If I hadn’t worked at the New Yorker, I’m not sure that I would have known that the Fund for Investigative Journalism exists, and I would likely not have been able to take the risk to pursue this story full-time. There are so many stories to pursue, and it should be the responsibility of funders and publishers, as well as journalists themselves, to make sure that the reporters who are best suited to write them are aware of the opportunities that make that work possible.