Heat kills. And in the United States in the past decade, heat has killed nearly 400 workers — mostly people of color — who were employed in often-grueling outdoor work collecting trash, picking crops and constructing buildings.

But it took a team of investigative reporters from Columbia Journalism Investigations and National Public Radio, with support from the Fund, to focus on the perils of working in the heat to attract government attention.

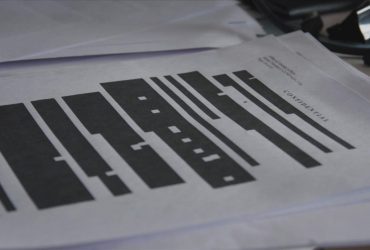

The reporters reviewed hundreds of pages of documents, including workplace inspection reports, death investigation files, depositions, court records and police reports. They interviewed victims’ families, former and current officials from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, workers, employers, workers’ advocates, lawyers and workplace experts.

The federal Occupational Health and Safety Administration is responsible for worker safety, but the reporters, from four media organizations and working in several states, quickly found that it had no standard for determining when it is too hot to work. Without a standard, the government is not specifically tracking workers’ heat-related illness and death.

What the reporters did have were thousands of OSHA death reports from across the country, many mentioning heat. Those reports spotlighted the dangers that people toiling in essential yet often invisible jobs face in 37 states across the country: farm laborers in California, construction and trash-collection workers in Texas and tree trimmers in North Carolina and Virginia. The reporters also found and analyzed another source — federal data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics — that showed the three-year average of worker heat deaths has doubled since the early 1990s.

The reporters and their editors were able to tag the data related to heat, providing leads that would take the reporters to families and friends of the deceased workers, and also helped them zero in on about a dozen companies that had had several worker deaths in recent years.

The team found that workers of color have borne the brunt of heat-related workplace deaths. Since 2010, Hispanics have accounted for a third of all heat fatalities, yet they represent a fraction — 17% — of the U.S. workforce. Health and safety experts attributed the disproportionate findings to Hispanics’ overrepresentation in industries vulnerable to dangerous heat, such as construction and agriculture.

OSHA has known about the dangers of heat — and how to prevent deaths — for decades and in the past has proposed safety measures, including frequent breaks and ready access to water. But the agency has not acted on its findings, citing other regulatory priorities, the reporters found,

Early on in the reporting, it was clear that there would be language barriers, cultural differences and distrust of journalists. But the reporters employed old-fashioned journalistic shoe leather to get to the sources. They found advocates willing to take them into the fields to talk with workers. They knocked on doors, placed hundreds of calls, sent emails and made contacts via social media. For the most difficult sources, it required going back, again and again, to build trust.

California is one of a handful of states that has its own heat standard for the workplace, but the reporters found limited enforcement. In 2019, for instance, the agency conducted more than 4,000 heat inspections and cited workplaces in nearly half of them. Still, the reporters’ analysis shows that California’s yearly tally of worker heat deaths has remained steady over the past decade.

Within weeks of the story airing on NPR, President Biden announced an “all-of-government effort” to address the problem, which will include inspections, enhanced enforcement and a new federal rule to protect workers from heat. For the first time, OSHA is officially considering a heat standard by putting it on its regulatory agenda. James Frederick, OSHA’s acting director, said it’s a “priority” for the Biden administration.

Christina Stella, a reporter with Nebraska Public Media; Jacob Margolis, a reporter with KPCC in Los Angeles; Allison Mollenkamp, an intern on NPR’s investigative team; and The Texas Newsroom contributed to this story. Julia Shipley, Brian Edwards and David Nickerson reported this story as fellows for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School in New York. Cascade Tuholske, a climate impact scientist at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, contributed to the data analysis. Public Health Watch, an independent investigative nonprofit, helped edit the story.